Speech written by KRUPP for the occasioh of an invitation to the UNIVERSITY of BERLIN during JANUARY 1944, but not

delivered.

"Thoughts about the Industrial Enterpriser"

[Resume of first 11 pages]

[Krupp goes into lengthy details about the human qualities and considerations that are required of leading men of Industry.

He points out the characteristics of leadership, and the necessity for sufficient industrial and financial background to fill a leading position.

From there Krupp leads to the idea of "being born for leadership", and affirms his belief in a dynasty of industrialists. This leads to a discussion about the merits of armament factories and armament "Kings" for one's own country, and finally Krupp continues : ]

"Therefore, I don't see why this thought still flutters in many a head occasionally—that the production of war materials should be a sinister trade! No: war material is life-saving for one's own people and whoever works and performs in these spheres can be proud of it; here enterprise as a whole finds its highest justification of existence. This justification—I may inject this here— crystallized especially during that time of the "Interregnum", between 1919 and 1933, when Germany was lying-down disarmed. I have already often repeated orally as well as in writing, and today I also want to restate to this group that, 'according to the terms of the Dictate of Versailles Krupp had to destroy and demolish considerable quantities of machines and utensils of all kinds. It is the one great merit of the entire German war economy that it did not remain idle during those bad years, even though its activity could not be brought to light for obvious reasons. Through years of secret work, scientific and basic ground work was laid, in order to be ready again to work for the German Armed Forces at the appointed hour, without loss of time or experience. This required many and various things, this demanded also the introduction of specific products suited to maintain the skills of experienced engineers and war-workers—this tremendous fund of knowledge and experience ; this required further the equipping and maintenance of scientific laboratories and research establishments etc. etc.

Just as once 100,000 men kept up the tradition of the old glorious Army so there also was—figuratively speaking—a 100,000

21

0—317

men army of business men who kept up the tradition of war industry. The circumstances caused by the military collapse were even more difficult considering the necessary changes in old war plants to peacetime production, which in itself caused untold difficulties in politically confused times. It was necessary for instance, to expand the Krupp Works into a structure capable of survival and competition, but, at the same moment they also had to be ready as war plants for future times.

Only through this secret activity of German enterprise, together with the experience gained meanwhile through production of peace time goods, was it possible, after 1933, to fall into step with the new tasks arrived at restoring Germany's military power (only through all that) could the entirely new and various problems, brought up by the Fuehrer's Four Years Plan for German enterprise, be mastered. It was necessary to exploit new raw materials, to explore and experiment, to invest capital in order to make German economy independent and strong; in short, to make it war worthy. On the basis of various remarks of outsiders, who are able to overlook the entire situation from a vantage point, I may well say that German enterprise proved itself here again, by tackling and solving the new problems with that energy, that— I might say: enthusiasm, with which it has always approached historical tasks.

In this connection I want to bring to attention something else, something which probably has hardly been considered in other circles so far: That is the fact, that the proven success of the Four-Years-Plan, the creation of new raw materials as substitutes for scarce ones, something which at the beginning showed only the quiet and modest degree of success we had hoped to achieve, (brought about) that not only were the well-known materials fully replaced in the customary field of usage, but that the new raw materials go many times far beyond their conception as substitutes for many uses—I am almost inclined to say: can be moulded fully as one wishes. That applies to artificial rubber, to synthetic gasoline and to various other similar things, and opens new vistas for the future which cannot be envisaged today.

After 1933, the German businessmen did not undertake such historical tasks of greatest range and scope only in organizational, technical and commercial respects.

The National-Socialist Revolution has hardly ever brought another profession face to face with such in many ways new—sometimes fortunately shockingly new—situations, as it has the enterpriser. Now he became the Fuehrer of his employees. It would

22

0-31?

of course be extremely unjust to claim that even before 1933 the enterprisers did not also have an understanding for this side of their profession leading and caring for people—for how could they otherwise have gained economic success in the long run? Particularly that is the pride of so many large enterprises, that they can look back to a rich and old social-political tradition, and yet, before 1933, it was made—God knows—many a time quite difficult for the enterpriser to act and show himself as the deeply responsibility-conscious leader of his business. This change since 1933 which occurred with almost elementary suddenness, concerning the conception about the spiritually founded partnership of interests between employer and employee. I am again making use of this old formula intentionally should be attributed to the singular genius of the Fuehrer and to his revolutionary movement, the Fuehrer who won through the power of his personality and his doctrines the whole of the German people to his expounded ideas of National Socialist ideology. It is clear that through them by appointing the enterpriser as Leader of his employees by law, a much wider and nicer, more promising field of activity than before was assigned to him, full with success especially concerning the human aspect—and I think I may state here, that the German enterprisers followed the new ways enthusiastically, that they made the great intentions of the Fuehrer their own by fair competition and conscious gratitude and became his faithful followers. How else could the tasks between 1933 and 1939 and especially those after 1939 have been overcome! Not by force, but only through good will—more so: only through devotion and enthusiasm could and can tasks of such world historical scope succeed."

[Resume: Krupp then lists the social achievements of National Socialism that were interrupted by the War and continues to speak about the team work of employer and employee under conditions of War.

Another paragraph speaks about the position of the enterpriser in public life, and then Krupp continues: Page 20]

"Into the future, I think, and this you probably felt too, due to my previous statements, the German enterpriser may look with full confidence. He will be even more necessary in the political, economic and social structure of our Greater German Reich after the War. I don't feel called upon to act as a prophet, but yet the grand vision of a New Europe floats happily before my eyes, and in this great space, which will then overflow with new economic, technical, transportation, commercial and financial problems of

23

D—317

all kinds—in this New Europe one will not only need farmers, frontier-guard-peasants and tradesmen, state and private officials, but in all countries and provinces as well, daring enterprisers ready for decision. And again people will say as before, during my time in Peking in 1900: 'Germans to the Front!' The German enterpriser will have to be the model for the new type of European enterpriser—j ust as the German worker will determine the future type of the European expert worker."

Summary of the text of a speech, on the value of the armaments industry, the secret work to prepare for Germany's rearmament, the enthusiasm of businessmen for Hitler's leadership, and the future of the post-war economy

Authors

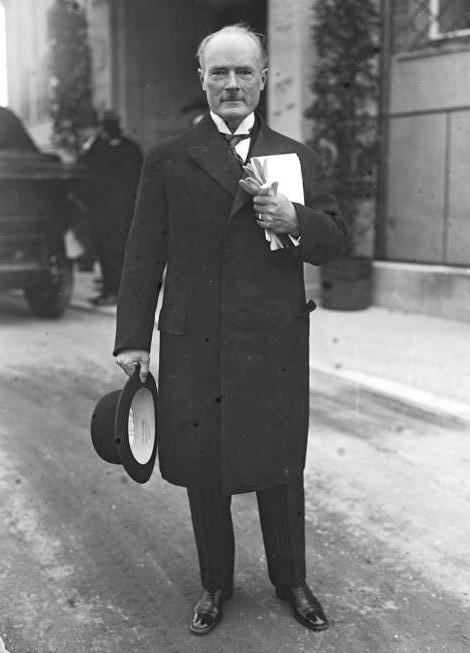

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (Krupp Works)

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach

German businessperson, politician (1870-1950)

- Born: 1870-08-07 (The Hague)

- Died: 1950-01-16 (Castle Blühnbach)

- Country of citizenship: Germany

- Occupation: banker; diplomat; entrepreneur; fabricator

- Member of political party: German People's Party; Nazi Party

- Position held: member of the Prussian House of Lords

- Educated at: Heidelberg University

- Spouse: Bertha Krupp

Date: January 1944

Literal Title: "Thoughts about the Industrial Enterpriser"

Defendant: Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach

Total Pages: 3

Language of Text: English

Source of Text: Nazi conspiracy and aggression (Office of United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality. Washington, D.C. : U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946.)

Evidence Code: D-317

Citations: IMT (page 289), IMT (page 5124)

HLSL Item No.: 450560

Notes:The speech was prepared for the University of Berlin, but was not delivered.

Trial Issues

Conspiracy (and Common plan, in IMT) (IMT, NMT 1, 3, 4) IMT count 1: common plan or conspiracy (IMT) Nazi regime (rise, consolidation, economic control, and militarization) (I…

Document Summary

D-317: Speech written by Gustav Krupp to be delivered at University of Berlin entitled 'Thoughts about the Industrial Enterpriser'